Saturday 28th February 2026

Open Mon-Sat, 10am to 4pm. Closed Sunday and all public holidays.

Saturday 28th February 2026

Open Mon-Sat, 10am to 4pm. Closed Sunday and all public holidays.

Tucked away in a corner of the Australian Muslim History section of the Islamic Museum of Australian is an almost whimsical painting of a Malay pearl diver by Riki Salam. With connections to Muralag, Kala Lagaw Ya, Meriam Mer, Kuku Yalanji peoples on his father’s side and Ngai Tahu peoples on his mother’s, it may surprise some that his heritage is intimately connected with early Muslim Australian history. The pearl diver represented in the painting is Salam’s great grandfather, Hardie Salaam Snr., who was born in Malaysia and moved to Australia to work as a pearl lugger during the 19th century. The vibrant collection of turtles, crayfish, trochus shells and sea cucumber represent the past trade between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders with the early Malay and Makassan people. Despite the dream-like quality of Salam’s art, the undulating waves of the ocean and the swirling chaos surrounding Hardie’s helmet speak to a more complex history of colonial racial discrimination and indentured servitude. History of Muslim pearl divers is a part of Australian heritage which has sunken deep into the margins of Australia’s collective memory, however once you dust off the sea debris it becomes glaringly obvious that the history of Muslim Pearl Divers is much more than just a blip in Australia’s economic policy. Underneath the copper and brass helmets are Muslim-Australian stories of perseverance against immigration restriction and their contribution to early labour activism, war efforts and cultural enrichment.

The history of pearl-shell trade in Australia dates back to the early 19th century, however, Southeast Asian divers and traders had been making regular voyages to the Australian coastline in search for pearls, trepang (sea cucumber) and sandalwood long before British colonialism. Highly developed maritime networks of pearl-shell fisheries, trading ports and communities encompassing southern Philippines, eastern Indonesia and areas of Malaya were seen as a profitable commerce prospect to the Australian Colonial Office in 1823, indicating the beginning of Australian and Muslim cross-cultural exchange. The industry relied on blackbirding of Indigenous Australians up until the 1870s where the Western Australian government imposed legislative bans on Aboriginal women as divers and aimed to regulate the use of Aboriginal labour, marking a shift to Asian labourers as primary divers. By 1875 a total of 1,800 Malays were employed throughout Northern Territory, Western Australia and Queensland. Due to the lucrative nature of the pearling industry pearl divers were exempt from the White Australia Policy immigration restriction act in 1901 and as such from 1902 to 1910 there were 7,788 Malays employed in WA alone.

LABOUR ACTIVISM AND MARITIME PROTEST

Despite the emphasis on slavery, Muslim pearl divers demonstrated a sense of maritime labour community and solidarity which refutes the myth that labour activism stemmed from a purely Eurocentric effort and postulates that it was the acknowledgement of Malay transnational flow of ideas. In 1912, the Western Australia Pearling Act set out penalties for breaches of disagreement, desertion and insubordination including punishment by imprisonment or forfeiture of accrued wage. When twenty-eight men from Koepang refused to sign the pearling contracts they were declared prohibited immigrants and jailed until they agreed to sign. Treatment of Muslim pearl divers was also underpinned by notions of racial hierarchy, often reporting that the pearl shell industry was unsuitable for white divers and that ‘the life [was] incompatible with that a European worker is entitled to live.’

Despite legal attempts to suppress worker activism, joining unions and protesting low wages was a form of directly opposing the colonial project. During the 1930s where Japanese divers were sought out over Malays, Malays began seeking advocacy via the North Australia Workers’ Union. The union essentially behaved as a protector of Malay indents, working in dialogue with labourers and doing their best to negotiate for better working conditions. Similarly, in 1950 the Indonesian embassy contacted the Australian Department of Interior about low wages, overcrowded living conditions and the shameful state of their labourers. Two years later the embassy was successful in getting the department to grant permission to indentured labourers to leave during the lay-up season on the condition that they would return to Australia. Cases of transnational diplomacy illuminate our understanding of the extent to which labourers could exercise influence even within restrictive colonial frameworks on a local and state level. When retelling these stories, we must be wary of suggesting that Muslim labourers were completely helpless to exploitation as these ideas rest on a racialised colonial notion that Asians were inherently vulnerable. Instead, as demonstrated by their involvement in international affairs, organised protests and labour activism, Malay pearl divers were not just a core component of Australia’s economy but were also active agents in shaping their communities.

WWII CONTRIBUTIONS

Another understated contribution of Muslim pearl labourers in Australian history is through war efforts. After the attack on Pearl Harbour 8 December, 1941, Australia made a formal declaration of war on Japan, putting a stop on the pearling industry. As such, Malay indentured labourers were moved from North of Australia down south. Aboriginal-Malay families were also evacuated from Thursday Island to Cairns to work on cotton and peanut farms for as low as one pound a day. Unable to leave their dormitories and regarded as potentially dangerous, many continue to engage in strikes and protests of low wages and working conditions.

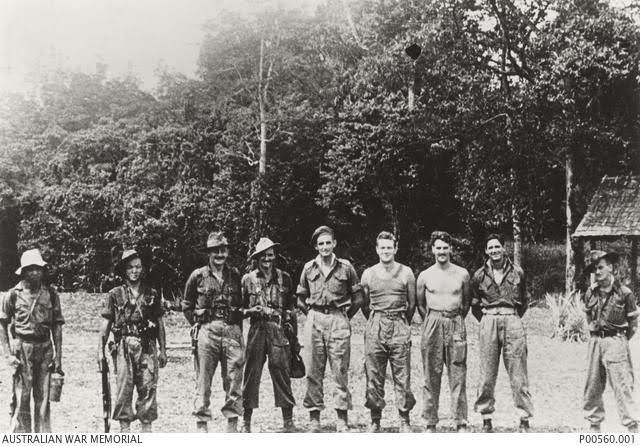

Although enlistment was restricted to European men initially, many Indigenous and Malay men were later recruited. ‘Z Force’ was a services reconnaissance department set up by General MacArthur to coordinate intelligence gathering in the Southeast Asian theatre during WWII. Malay men, the generic term used to encompass Filipinos, Chinese, Indonesian and Malays, were viewed as advantageous for their expertise of the language and knowledge of the water currents and were used to on rescue missions and well as in direct attacks against the Japanese. A European Z Force member, Rowan Waddy says that during his service: “We learnt to speak Malay, we had Malays there and everywhere we went you to be able to speak Malay.” Because of the discreet aspect of Z Force and many other military operations during WWII, the role of Muslim’s is not publicly acknowledged.

Malaysian born Abu Kassim bin Marah arrived in Broome in 1933 as a teenager. Working as a pearl diver and living with his Indigenous partner and daughters, he was assigned to the ‘1044 Z Special Unit’. He was involved in guerrilla warfare, hand-to-hand combat and gathering intelligence in Borneo. His name is displayed along with his team in the ‘Virtual War Memorial of Australia.’

In attempts to dismantle legacies of the White Australia Policy, it is important to keep these stories alive. For many of these men like Kassim, their freedoms were withdrawn at the end of the war and threatened with deportation, further highlighting the need to recognise their sacrifices.

IMPACT ON ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIANS AND CULTURAL LEGACIES

Postwar saw the return of Malay labourers back to work. Partially in effort to seek naturalisation and avoid deportation, Malay immigrants tended to marry and mingle with Indigenous peoples in Western Australia but not without difficulties. Long-term Muslim residents on Thursday Island even with Australian-born children could not make a case for citizenship. It was not until June 1957 when permanent residence and citizenship was extended to non-Europeans on the condition ‘of good character; had not wilfully disregarded the conditions of admission; had an adequate knowledge of English; and had taken part in normal Australia life.’ In 1958, nineteen Indonesian nationals were granted Australian citizenship and over the next nine years, 142 Indonesians were naturalised and granted the right to vote.

Sherena Bin Hitam, an Aboriginal Malay local of Broome recalls how Broome was segregated in the early pearling days but ‘the Koepangers, Malays and Indonesians… were more inclined to mix with the local Aboriginal peoples and … most of the Malay men have got wives, Aboriginal wives.’ As a result, there is a generation of Aboriginal-Muslim people contribute to the colourful social fabric of the town. Cultural merging of Muslim traditions such as tombstone unveilings inspired by the Islamic tradition of wrapping the body of a deceased person in white cloth before burial, Ramadan festivals, Hari Raya (Eid ul-Fitr) and the erection of Mosques from 1930s exemplify the creation of ethnic and religious networks in resistance to the White Australia Policy. Many Indigenous Muslims spoke out about the benefits they felt from their religious upbringing in giving them a sense of control over their lives. An Aboriginal-Malay reflects:

“It taught us to be visionary, it taught us to aspire to something, to achieve something, to make something of yourself… Little basic things that taught a lot of children of Aboriginal-Malay heritage to be able to go to that next level”

The stories of Indigenous Australian-Muslim marriages are a testament to the endurance of families who survived the dual burden of immigration restriction and racial discrimination. By digging a little deeper we can also appreciate the complexities of identity of Australian citizens and their contribute to a rich cultural history. In recognising these stories, we can challenge the notion of the White Australia as the main narrative and honour the contribution and persistence of Muslim Australians today.

Standing in front of this painting, viewers are invited to pause and reconsider what constitutes national heritage. It urges us to confront the silences in our collective memory and uplift the histories that live on in places like Broome, Thursday Island, and in the families born of cross-cultural solidarity and survival. Salam’s artwork invites you to uncover the pearls of our shared history - stories that shine, not in spite of being buried, but because someone chose to bring them back to the surface.

Visiting the Islamic Museum of Australia offers more than a chance to see this artwork; it invites you into a space that challenges mainstream narratives and celebrates the rich, multifaceted contributions of Muslim Australians. From art and architecture to science, spirituality, and sport, the Museum showcases the diverse ways Islam has intersected with Australian life for centuries.

Rosalie Tran is an undergraduate student at the University of Melbourne studying History. She interned at the Islamic Museum of Australia from August - October 2025.